|

FROM THE SHADOWS OF WAR - AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY - BY RAY KEMP |

|

THE

FOLLOWING ARE THE DRAFT EXTRACTS FROM RAY’S AUTOBIOGRAPHY THAT HAVE BEEN

SELECTED BECAUSE THEY CAPTURE MEMORIES OF INCIDENTS AND PLACES IN

TOTTENHAM. TO HELP FURTHER UNDERSTANDING OF THESE MEMORIES WE HAVE

ADDED A NUMBER OF PHOTOGRAPHS TO ILLUSTRATE THE SUBJECT MATTER. |

|

MY EARLY MEMORIES My first real memories on planet earth are of

steam trains, the royal family, the glorious game of football and

poverty. In their own unique ways, they all played a very important part

in my life. One of the first sounds I can remember was Spurs

scoring a goal. The cheers from the crowd crammed into the football

stadium at White Hart Lane were just audible above the noise of an

ageing locomotive train whistling its way past my home en route to the

nearby Seven Sisters junction. The house into which I was born was a good two

miles from the football ground. But when Tottenham Hotspur scored a goal

the noise from the crowd carried on a stiff north wind could clearly be

heard as the sound shook the rickety sash windows of my Victorian

terraced home. If it was an evening match the flickering floodlights

from the ground would light up the smoky sky and the cheers would seem

even louder as I snuggled down into my bed pulling the rough, ex-army

blankets around me trying to keep warm. I was probably still in my cranky old pram with

its big hood and rusting wheels when I first heard the cheers. But over

the years I would stand countless times with my dear old dad on a

Saturday afternoon cheering on the “Lilywhites” while cracking the

shells from a bag of Percy Dalton’s roasted peanuts clutched tightly in

my freezing cold hands.

“While

my mum had a difficult war my dad fared no better. At the beginning of

the war my dad’s home was a small and cramped two bedroomed terraced

cottage in Tottenham’s Summerhill Road. He lived there along with my

grandparents and his two unmarried sisters, Vi & Olive.” “The hearts of my fellow Londoners were big and

generous. For many their shoulders were heavy having suffered terribly

during the Blitz. They were good, hard working people whose lives had

been tough and rough. In the main they were very honest and they were

also very smart. Today nothing makes me angrier than to see plays and

films from the fifties – and even more recently - made by snooty

producers and directors who had lived cushioned, privileged lives making

fun of the working class who were the backbone of London and who worked

to make it one of the greatest cities in the world. |

|

CORONATION MEMORIES My first real memory was not of football but

of the royal family. I suspect that it was more than fortuitous that my very earliest memory of all was as a one-year-old being held in my mother’s arms at a street party held to commemorate the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. |

|

|

CORONATION STREET PARTY SEAFORD (LITTLE) ROAD |

|

It was wet on the day, so the celebrations

planned for the streets were held instead in the wooden stairwell

leading up to the platforms of Seven Sisters station. I can remember the

union jack bunting strung from the ceiling over the lines of trestle

tables. Rationing was still in force in 1953 so the bright green

jellies, the frosted biscuits and the luxury items on the tables would

have meant real sacrifices for the families involved to make sure the

day was truly memorable. RAILWAYS It is not surprising that steam trains played a

big part in my life for most of my childhood because my dad was working

on the railways. With his big, strong hands and powerful shoulders

before the Second World War he had been a platelayer. The job involved

working with large teams of men lifting heavy steel rails by hand into

place on top of the rough wooden sleepers. In those days there was no

automated machinery to help them put the rails in place. |

|

|

|

SOUTH TOTTENHAM STATION 1950s - WAITING FOR SOUTHEND TRAIN |

|

The big highlight of the year would always

be a trip to Southend. Along with hundreds of other passengers we would

stand on the crowded wooden platform of South Tottenham station waiting

for the train to take us to the seaside. The trip meant a change of

trains at Barking and there was always a rush as the locomotive pulled

in from London’s Fenchurch Street to try to get a seat on the train. |

|

|

COME ON YOU SPURS !

MY INTRODUCTION TO BEING A LIFETIME SUPPORTER |

|||

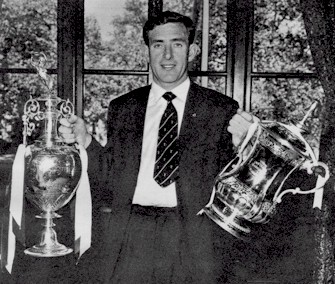

SPURS CAPTAIN DANNY BLANCHFLOWER 1961 |

|

||

|

|||

|

But, just like life, football is a game of highs

and lows and after the happiness of victory the sadness of defeat often

follows. One of the saddest nights of my life was when Spurs were

knocked out of the European cup by the Portuguese side, Benfica. As I

left the ground with thousands of other slumped shouldered supporters it

was one of the longest and hardest walks home as I made my way from one

end of Tottenham to the other. |

|||

|

ORIGINAL TICKET & PROGRAMME -Alan Swain |

|

|

|

In

my teenage years I would go to the ground with Barry Troyna one of my

best mates. Often the fighting on the terraces was more entertaining

than the game on the field and we would be more interested in counting

the numbers arrested than the goals being scored.

|

|||

|

BATHDAYS AND WASHDAYS

|

|

|

All five of us in my family, my brother and sister, my mother and I

would use the same bath with my dad always being the last to step into

the already dirty and by then tepid water. Occasionally when he was very

dirty, he would go to the municipal public baths but with money in such

short supply they were a luxury as a family we could ill afford.

If it

was a hard life for men it was just as hard a life for women. Keeping

clean was a constant problem. My mum had been brought up in the Sussex

countryside where the air was pure and fresh, and clean water was always

available from the springs and wells of the High Weald. |

|

Apart from the notorious London smog which hung

around for days and coated men, buildings and horses still pulling carts

through the streets with yellowish black soot we lived near to a railway

junction. Sometimes on washdays my mum would hang the heavy linen sheets

and the clothes of a family of five on the line. No sooner were they all

carefully pegged in place than a train making its way from Alexandra

Palace to Stratford East would be held up by a semaphore signal at Seven

Sisters junction.

|

|

|

Once the heavy washing had been pegged and

unpegged and then brought into the house it all had to be ironed from

the sheets to every tiny handkerchief. In those days no self-respecting

housewife would allow a single item of laundry to remain un-ironed. On

wet winter days the washing would have to be hung on a clothes horse

around the open fire with the ever-present risk that a cinder would spit

out from the flames and catch the clothes alight .... or at best burn a

hole in a prized skirt or cardigan. |

|

|

THE COALMAN |

|

|

With the weight of the sacks on their shoulders the coalman’s heavy hobnail boots also left dents in the lino where they walked. In those days it was hard for a woman to be house proud and fitted carpets were an unheard-of luxury for in any case they would have been ruined by the boots. |

|

TOILETS AND SANITATION |

|

|

As a three-year-old I can remember sitting in

the toilet with agonising stomach pains desperately calling out for my

mum. She was in the kitchen at the other side of a yard. There were two

doors in between, and she could not hear my cries for help. It was a

long time before she came to see where I was and then realised I was

seriously ill. |

|

|

MUM’S WARTIME EXPERIENCE |

||

|

|

|

|

When the war was over my mother was invited to Buckingham Palace where she was presented with Fred’s Distinguished Flying Cross by King George VI.

|

||

|

MY DAD’S WARTIME EXPERIENCE Somewhere along the line a senior officer must

have realised that my dad was a very gentle soul who would not want to

kill anyone. Faced with a German soldier in his rifle sights he would be

one of the least likely of human beings to pull the trigger. |

||

|

||

|

The medics during the

D-day landings have been described by the historian and writer Max

Hastings as “the bravest of the brave” and from some of the stories that

my dad has told in his modest, quiet way I am sure that he was.

Within six weeks of landing on the

beaches he was seriously injured when a shell exploded beside him and

killed his best friend.

After Germany was defeated my dad remained in

Hamburg with the army. He did have a German girlfriend while he was

there. But his last and final memory of his girlfriend was her being

taken away on a Russian truck when they moved into the sector as British

troops moved out. He never heard from her or saw here again. |

||

|

POST WAR TOTTENHAM When he was demobbed my dad returned home to live with my grandma and grandad in Summerhill Rd, |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

Tottenham. His young

son Roger had been looked after by his maternal grandparents and Alf

Kemp was unhappy with the conditions that his son was living in with his

wife’s relatives so brought him back to live with my grandparents in

Summerhill Road.

So

there they all were my two maiden aunts, my dad, my brother and my

grandparents all living together in a tiny two bedroomed cottage It was not until well after the war that my

mother met my dad, Alfred Kemp. They had met because her then

work-friend, Elsie Kemp, introduced her to Alfred. (The younger brother

of her husband Will Kemp) So, it was through Elsie that my mum and dad

met and in 1948 they were married in St. Margaret’s church in the

grounds of Buxted Park in East Sussex. My mum was born Nellie Muddle and

for five hundred years the Muddles had lived in and around the villages

and hamlets in the heavily wooded and beautiful Sussex high weald.,

THE STREET WAS MY PLAYGROUND |

|||

|

|

||

|

The best playground was the school opposite my

home. At night we would climb the walls and break into the school.

Sometimes we would walk along the roof tops. The outside lavatories at

the school had glass roofs. One slip as we walked along the edge and we

would have fallen through the glass with possibly deathly consequences.

|

|||

|

THE WINTER OF 1963 For the next few weeks, the streets of London were covered in snow. There were great piles of dirty snow in the road where householders had scraped it off the pavement. Just before Christmas my poor old dad had bought his first car, a second-hand Ford Popular. But there was his pride and joy stranded in the snow out in the street. The battery soon ran flat because the car did not move. Every so often he would go out and use a starting handle which he inserted into a special hole in the front of the car. Sometimes the cranking would work but sometimes the engine just would not start. He had put old coats on the inside of the engine compartment to try to stop the parts from freezing. |

|

|

|

|

On

one occasion he cranked the engine to start it forgetting that he had

left the coats lying over the engine. Unfortunately for him on this

occasion the car did start. It was only when wisps of smoke started to

blow out from the engine compartment, he remembered that he had not

removed the coats. He very nearly lost the car in a blaze of glory on

the snow-covered road. |

|

|

|

|

END OF SWEET RATIONING |

|

|

|

|

The lucky bags contained a surprise variety of

sweets which could include sherbet dabs and liquorice wheels. But my mum

always told me not to buy them because it was rumoured they were filled

with sweets swept off the factory floor. Around the corner from where we lived in Seven

Sisters Road there was also an old-fashioned sweet shop where my dad

would sometimes take me as a special treat. The sweets were made on the

premises. I would watch with fascination as the shop owner pulled out

long strands of hot, sticky cough candy canes from an oven and cut them

into mouth size pieces. My dad would buy a bag of still warm candy and

share a piece with me as we walked home

.There

were several sweet factories not far from where we lived. They included

the brands Maynards and Barretts which are still around today. But when

I was very young my uncle Will worked at the Clarnico factory in

Hackney. The only sweets I had as a child from a big tin were misshapes

which he gave to my family. My mum gave them to me as a small child and

it meant I soon had very bad teeth. |

|

|

LOCAL PARKS OF TOTTENHAM |

|

|

|

|

In the adjoining

Lordship Recreation Ground there was a model traffic area where children

could hire bikes and model cars. There were real traffic lights and real

policemen and it was where I learnt to ride a bike. In those days we

were too poor for me to own

a bike of my own.

The model traffic area had been opened a year before the war. |

|

|

WARTIME BOMB SITES Of course, we should not have been on the old

bomb sites but we were skilled at breaking and entering and climbing up

and over fences. The other areas we often broke into were the railway

embankments. We would climb on each other’s shoulders to get over the

walls and fences and then pull the person still standing on the pavement

up and over |

|

|

One of our favourite pastimes was train

spotting. We would sit for hours on the embankment overlooking Finsbury

Park station watching steam trains racing by on the tracks below ….

steaming their way to towns and

cities we have never been to but had only heard about. Strange places

like Derby, York, Leeds and Edinburgh. |

|

|

|

|

We had tattered, dog eared books full of the lists of locomotive numbers that were published by Ian Allen. Sometimes just one locomotive in its class would be missing from our list and it felt like a real triumph when we finally spotted the train and could add it to our list. The railways and the railway embankments were exciting places for us to play. Often, we climbed over walls and fences for there was little to stop us. There were plenty of “Do Not Trespass” signs which we always ignored. We would often be no more than a few feet from the lines as steaming monsters raced by.

|

|

|

THE END OF STEAM TRAINS |

|

|

|

|

We

didn’t realise then that it would herald the end of the steam trains we

loved so much. The only diesels we knew up until that time were the

little engines that shunted carriages in and out of the marshalling

yards. Meanwhile in Whitehall Dr Beeching was swinging

his blunt axe cutting railway lines and isolating towns and villages

that never really recovered from losing their stations. |

|

|

LOCAL SHOPS IN WEST GREEN |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

There was also the “Swap Shop”. Its windows were covered in bright red metal grilles and just looking through them was an adventure in itself. There were military swords and helmets, binoculars, cricket bats and golf clubs, garden tools and medals. All seemingly piled together and displayed in no particular order. There were also a number of guitars and air guns and rifles. I still have the guitar I bought from this shop and as for the air gun ... well it had quite a good range.

Alongside the more conventional shops there was a record shop called Dyke and Dryden. It was owned by Jamaican immigrants and is credited with being the foundation stone for being the first multi-million-pound black business in the UK. With music blaring out of the door and its colourful window display it was certainly different from any other shops at the time. |

|||

|

ALEXANDRA PALACE As I grew older one of the favourite places my mates and I liked to play was in the grounds of Alexandra Palace. From my bedroom, as I went to sleep at night, I could see the red light from the 600-foot-high BBC transmitter at Alexandra Palace as it beamed out news bulletins around the world.

|

|||

|

|

|

||

|

The

palace was a cycle ride away. By the time I was about nine I had a bike

of my own. My dad bought it for me from a second-hand shop and it gave

me the freedom to explore further afield than the immediate streets in

my neighbourhood. |

|||

|

MY FIRST BIKE |

|

|

HETCHINS BICYCLE FRAME WITH UNIQUE REAR WHEEL ASSEMBLY |

|

Most of the boys I knew had second hand bikes

and it was a constant battle to keep them in good repair. From an early

age I learned how to put in a new chain link, grease a sprocket, replace

worn ball bearings and mend the frequent punctures. The bike shop of our

dreams was Hetchins on Seven Sisters road. A Hetchins bike had won the

1936 Olympics and we would stare in the windows at the glistening

hand-made frames on display there. |

|

|

ALONG THE RIVER LEA

|

|

|

|

|

Two

days before my 15th

birthday I was woken by my brother, Roger, in the middle of the night

and told to look out of the window. The whole of the sky seemed to be

alight as the largest of the Bamberger woodyards burnt to the ground.

Roger was by then a London fireman. He had been sent home exhausted

after fighting the fire for over eight hours. Over 400 firemen and 50

fire engines spent three days fighting the fire which is thought to have

been started by an arsonist. |

|

|

|

| EDITORS NOTES: These extracts

have been taken from Part One of his Biography and largely concentrated

on his early Tottenham memories. However, Ray has written Part Two

of his Biography that concentrates on his lifetime experience as a TV

journalist . Both of his books are available from Amazon and, in addition to a copy of the front cover for his second book 'Life Through The Lens', readers will I am sure be interested to read their 'Thumbnail ' description of Ray's career in Newspapers, Television and Theatre. see below: |

|

| AMAZON

INTRODUCTION Born on the back streets of London by the age of fifteen Ray Kemp had appeared on the West End stage and BBC TV before becoming a journalist. His career as a newspaper and television reporter took him to the wilds of Dartmoor and Exmoor, the coasts of Cornwall and to the top of the mountains in the Lake District. For a time he travelled through the Borders of Scotland and Dumfries and Galloway before arriving in Brighton where he met and interviewed some of the most famous faces of his generation. In this first part of his autobiography Ray describes his childhood and growing up in a city where people and places were still badly scarred by the shadows of the war. He tells how as a student he was tricked into travelling to the USA with a religious cult before becoming a newspaper reporter in the West Country. There he witnessed at first hand smugglers and shipwrecks and covered one of the most famous murder attempts and political scandals of modern times. This is just as much the story of some of the fascinating men, women and children Ray met and interviewed as it is the tale of his own eventful life. In the second part of his autobiography Ray describes how he moved from newspapers into the world of ITV news.. Working on the newsdesk at Westward Television he was involved with stories ranging from a major plane crash in Devon, to earthquakes in Cornwall and the tragic loss of the Penlee Lifeboat and its crew. He describes how he became a TV presenter for Border Television covering stories in Cumbria, Southern Scotland, the Lake District and Northumberland. During his time in television Ray interviewed people from all walks of life ranging from Lords and Ladies in their stately homes, to Prime Ministers and murderers. During the last part of his TV career he was based in Brighton with TVS covering stories throughout Sussex, Hampshire, Kent and beyond. He flew in Concorde, witnessed Margaret Thatcher signing the Channel Tunnel agreement in France and was in Berlin as The Wall came down. He witnessed the tragic aftermath of an IRA bomb. Talked to some of the first victims of the Aids epidemic and filmed Princess Diana as she fell from grace. This is just as much the story of some of the fascinating men, women and children Ray met and interviewed as it is the tale of his own eventful life. |

| Article prepared for website using original text from Ray Kemp's Biography - Alan Swain Oct 2024 |